In Q4 2008, economy expanded 5.3%, slowest pace since Q4 2003, (Q3 2008: 7.6%, Q2 2008: 7.9%) due to contracting manufacturing (-0.2%), agriculture (-2.2%) and exports

Growth forecasts revised down: 2008: 7.8% (IMF), 7.4% (ADB), RBI: 7.5%; Govt: 7.1%, i-banks: 5.6-8%, RGE Monitor: 6%. Forecast for 2009: 7.1% (govt); 5.1% (IMF); 7% (ADB); I-banks: 4.3-6.3%, RGE Monitor: 5%

Since December 2008 Govt and central bank have been giving fiscal stimulus package aimed at non-bank financial corporations, infrastructure, housing, SMEs, exporters; reducing taxes, easing credit access. Since September 2008: Central bank continues inject liquidity, ease capital inflows and cut policy rates. Further rate cuts and credit easing, and fiscal stimulus expected in 2009 though close to 10% of GDP of fiscal deficit will limit the latter

Growth, capital expenditure and consumer spending in 2007/08 was fueled by global growth and liquidity boom, capital inflows and asset bubbles. But global credit crunch, risk aversion and Foreign Institutional Investor (FII) sell-off have severely affected domestic liquidity for banks, stock market and real estate correction, bank lending to finance consumer spending and investment. Domestic slowdown will aggravate asset market correction during 2009 and put bank performance at risk

Consumers hit by high inflation, tight lending standards, job losses, slower income growth, negative wealth effect from correction in stock and home prices

Recent boom in capital expenditure (37% of GDP) is being hit as manufacturing and industrial production are declining since December 2008; several investment projects are being canceled/postponed due to capital crunch; corporate earnings have also taken a hit since Q4 2008 on slowing domestic demand, tighter credit, volatile stock market and drying Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), global liquidity crunch that is limiting access to external finance (major source of capital); corporate savings will run down domestic savings while government runs a deficit

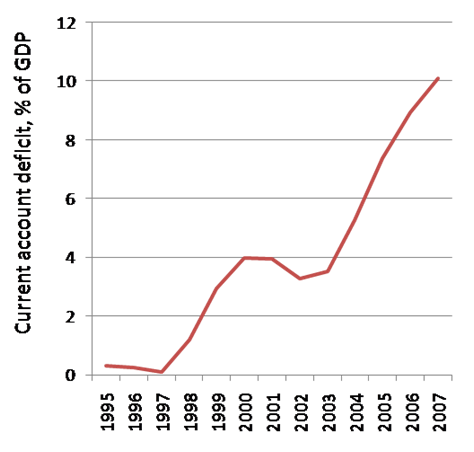

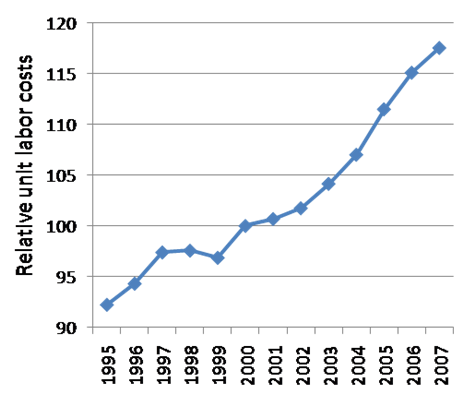

External Sector: Exports have been contracting since late-2008 since major export markets (US and EU) are in recession and high growth markets (Asia, Middle-East) are slowing. Financial sector woes in the West are affecting IT service exports. Vulnerability to trade and current account deficits (expected to exceed 10% and 3% of GDP respectively) on high oil import bill of 2008, contracting exports, slowing remittances from the West and Gulf. These factors pose risk to the current account while slowdown in capital inflows (FII outflow, easing FDI on risk aversion, global liquidity crunch) poses risk of financing external deficit. These factors have pushed rupee to a 5-yr low

Food and oil subsidies, pre-election and fiscal stimulus spending are expected to push fiscal deficit to 10% of GDP in FY ending Mar 2009 and over 9% in FY ending Mar 2010; S&P and Fitch have cut ratings to 'negative'. This may raise govt debt issues to over US$70 billion in 2009 raise interest rate and depress bond prices,putting risk of financing twin deficits at a time when capital inflows are already drying up

What others are saying

JP Morgan: Targeted 7.1% GDP growth in 2009 by government would not achievable, since fiscal packages in December 2008 and January 2009 and monetary easing in late-December 2008 need 6 or 9 months to show up in the growth rate

IMF: Significant downside risks to GDP growth in 2008 (6.3%) and 2009 (5.3%) but government measures could be an upside though constrained by the fiscal deficit and large public debt, thereby increasing dependence on monetary policy

Citi: While trend in auto, cement, steel and retail sales in February 2008 expected to be positive, real estate, freight and port traffic as well as march data are still worrisome; hard to achieve 7.1% growth in 2009

EIU: 7.1% growth in 2009 targeted by government is overly optimistic; Global deleveraging and risk aversion will limit the availability of financing for investment and consumption, which will increase the pain on industrial and services sectors; Despite of struggling by govt. to create enough jobs for labor force, number of unemployed workers would increase (500,000 jobs were lost in Oct-Dec-08); It will play the important role for election in April-09

Deloitte: India economy has been impacted by four different ways; weak manufacturing, falling exports, revenues of software companies and closing credit tap in banking sector

Morgan Stanley: Recent growth trend above sustainable levels was driven by capital inflows. Stimulus measures won't prevent a deeper slowdown in domestic demand, cost of capital, industrial production and exports

Kotak: India in a two-year cyclical slowdown with slowing saving and investment, but this phase may be short and shallow unless the global economy deteriorates more than expected. But new capacities in mining coming on-stream, large consumption stimulus, high domestic saving base will help sustain reasonable growth. The sharp deterioration in activity Q4 2008 may have got arrested in Jan 2009; fiscal package too small to sustain the current investment and growth cycle and is constrained by fiscal deficit; monetary stimulus will help reduce interest rates but pace of rate cuts will ease

Goldman Sachs :growth will reach a trough in Apr-Jun-09 before recovering by end-FY10; Stimulus would support specific sectors amid the downturn but not enough to reduce impact of slowdown on aggregate demand

WEF: Dependence on capital flows to finance current a/c deficit is a risk; global crisis could cause sharp capital outflows, fall in share and asset prices, reduction in availability of finance

Please do leave your comments. Would like to hear from your perspective also.

![[TradeExportsImportsJan2009.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjUYbRD9aJINcgvTNd1XJk_3tMQnNt7HNz0N244yvnjFZadnl2zR-FXDt07uXN7U9gQ98dI8mrMB2PHMWhCRb30YTz-tW5T3BlniaT_ziXiHFnPFOjgZSimefW6agaYwc9SfJVBnpF8hog/s1600/TradeExportsImportsJan2009.jpg)

![[TradeDeficitJan2009.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhCQfKmwKwf_ck_qm_p-QsgGvcpqvak7iDfpCJrRVvewDUDQ7OkGQ-r4a_tmcQ4x-gd-qNG_GgE9Rw2GAgxR3Fn8La26LN3VYxMdo5V6OFBBvoKzGYt87GfI3KhBNggN7C1yqvgql4EASw/s1600/TradeDeficitJan2009.jpg)